There is an unavoidable question in early B2B sales calls: “How much does it cost?” Any experienced buyer wants to figure out quickly whether to spend their time learning about our product. As part of that, they need a fast way to get a rough understanding of our price.

All B2B sales reps know that they have to answer the price question. While their initial answer may or may not be direct, it needs to be good enough  to get to the next meeting. The best sales reps know that they need to introduce customer value in the same answer, qualitatively or quantitatively. Great reps position our solution in early conversations based on what we deliver to our business customer – our solution’s value to our customer.

to get to the next meeting. The best sales reps know that they need to introduce customer value in the same answer, qualitatively or quantitatively. Great reps position our solution in early conversations based on what we deliver to our business customer – our solution’s value to our customer.

Eventually the price conversation is bound to be quantitative. No number? No deal. If price is what you pay and value is what you get, then the value conversation needs to be quantitative as well. Some member of the buying team will be doing the math. Sales teams need a way to talk about quantified price and quantified value if they are going to stay in the discussion with buyer teams.

Price, Value and Units. Any numerical answer to the price question has to be expressed in a currency. A clear, simple price answer has only two components, a number and a unit: $200,000 per year, ₤0.10 per part, €320 per procedure, $28.00 per pound, $x per unit. In most organizations, for most products, untold hours are spent discussing and refining the number x and how to calculate it in different situations. In too many organizations almost no time is spent considering the unit.

Yet units matter, in understanding customer value, in setting the price, and in communicating the cost and benefits of our product or solution. Units set the frame of reference for almost all conversations: internal discussions of the best pricing and marketing strategy, and external conversations  where sales teams engage the customer.

where sales teams engage the customer.

There are only two kinds of units: product-based units and customer-based units. If we quote our prices and deliver our product in pounds, kilograms, litres, gallons, machines, kits or records uploaded, talking about prices and value in those units is a necessity for forecasting and planning. They are a natural place for development teams and product managers to start. But product-based units drive conversations to a product-centric frame of reference that creates a set of challenges.

Customer-based units reframe the conversation to focus on the audience that matters: value per year, cost over the life of the equipment, savings per patient and revenue per part manufactured by our customer. Units like these transform the perspective to one that is customer-centric. The change in viewpoint that results has tangible benefits in internal decision-making and in customer conversations.

Customer-Based Units Make a Difference. There are three ways that framing discussions based on customer-centric units have an impact on business results. Using customer-based units helps teams to:

1. Communicate numbers that resonate with customers. If our sales teams are going to have meaningful conversations with customers, we need to be able to speak our customer’s language. Expressing numbers on a product-centric basis has a 99% probability that it will reduce the  number of stakeholders who understand the numbers we present. The C-suite, general management and finance professionals understand numbers that relate to their financial statements: “per quarter,” “per year,” “over the life of the contract.” Operating managers understand numbers that let them do quick math on their key metrics: “per part,” “per acre,” “per patient,” “per customer.”

number of stakeholders who understand the numbers we present. The C-suite, general management and finance professionals understand numbers that relate to their financial statements: “per quarter,” “per year,” “over the life of the contract.” Operating managers understand numbers that let them do quick math on their key metrics: “per part,” “per acre,” “per patient,” “per customer.”

Teams that fail to translate price and quantified value into customer-centric terms can count on a smaller audience. But the composition of that audience is often a larger problem. The single most likely person in the customer’s buying team to understand prices quoted in product-centric units is the procurement professional. Procurement’s playbook is based on product quotes and contract terms. Procurement teams pay for data sources and gather pricing intelligence quoted on a product-centric basis. They pull out information selectively to make their case and put sales teams off-balance. Some of them pay attention to value but they are schooled in the street smarts of when to play dumb and what to reveal to sales.

Expressing price in customer units is one counter to this problem. Expressing quantified value in customer terms is another response. But the best approach is to arrive at the procurement discussion with a business case to buy already agreed upon with a customer sponsor.This means discussing price and proving value in customer-centric terms with operating and executive stakeholders before the procurement process gets underway. CRM data from organizations adopting value selling show that opportunities where a Value Proposition is used have 5-15% higher win rates and 5-25% higher price outcomes.

The best B2B enterprises use Value Propositions collaboratively to improve B2B sales team performance, addressing sales challenges throughout the B2B sales cycle. For account executives and sales reps, Value Propositions are useful early in the sales cycle as Flexible Case Studies in call preparation, in building sales confidence, in qualifying opportunities and in engaging customer executives. They should be designed with customers and users in mind where increasingly customer-facing teams include both sales representatives and presales professionals. For technical sales and presales professionals, Value Propositions provide Customer Value Analyses as an important way maximize the impact of presales. As customers decide to purchase, the Value Proposition becomes a Shared Business Case, collaboratively agreed between sales executives and customer sponsors, that can be used by buyers as their own internal financial justification to purchase. If a Shared Business Case is the goal, then the best place to start is with customer-based units.

2. Understand our product’s impact on our customer’s business. We may quote prices in our product unit but this unit often has little to do with how our customers think about their business. Crop protection products are sold per pound, but growers buy them per acre. Production equipment is priced per machine, but the number of machines purchased is based on a manufacturer’s targeted production capacity. Software licenses may be sold per user, per month or per data record processed, but the organization using the software wants to understand the enterprise-wide impact of the software per year or over the life of a contract. Hospitals purchase and stock pharmaceutical vials, but hospital management wants to understand the drug cost per procedure.Prices may be quoted and managed in a product-based unit, but value is more naturally quantified in a customer-based unit. Keeping units straight is critically important to avoid confusion in quantifying value. Here is just one example to illustrate the point.

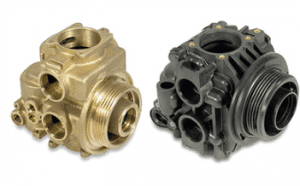

Illustrative Example: Superior Coating for Auto PartsWe sell a better coating to auto part manufacturers. We sell the coating by weight and quote prices per kg. Our superior coating results in more durable parts and the potential for higher part prices for our manufacturing customer. How would we quantify the value? Product Instead ask the question, “what is the part durability that comes from our coating worth to the manufacturer per part?” Even if our team doesn’t know the answer initially, the questions and hypotheses to arrive at answers are simpler. “How much does our coating extend the life of the part?” (months per part) There can also be questions for our customer’s customer in terms of a unit that matters to them – per vehicle. “How much is longer part life worth in reduced warranty costs to the auto manufacturer buying parts from our customer?” (based on parts per vehicle) These questions are naturally asked in the marketplace in terms of customer units: per part or per vehicle. These questions may have natural initial answers or hypotheses that we can find with 10 minutes of googling. Some of these questions are questions we can ask our customer’s customer on a specific basis as a way to make a stronger case to our direct customer. |

The business impacts of understanding value based on customer units are both general and specific:

- Build confidence in the math. The harder it is to understand a question, the harder it is to check the answer. The answer won’t make intuitive sense. The “increase in part revenue per pound of coating we sell” is not a number that anyone can check for plausibility. Even if the calculation is right, the math is unnatural and hard to explain, diminishing the team’s confidence in the value itself. Product management and pricing teams rarely set higher prices to capture value that no one on the team finds to be intuitively plausible.

- Understand the magnitude of our product’s impact on our customer’s business. Selling innovative solutions is usually harder than selling undifferentiated offerings. Buyers may need to change their approaches to marketing process, treating patients or producing products. We may have a better product that has a large percentage economic benefit, but if the absolute value is trivial to their business, it won’t move the needle enough to drive change. Customer segments where we don’t have meaningful impact are probably the wrong segments for sales and marketing spend. Some customer-based units may not help much in understanding the magnitude of our impact, but using an accounting period (per year, per quarter) usually provides perspective on whether we will be able to get a customer organization’s attention.

3. Capitalize on innovation that enables our customer to buy less product. More efficient products often make it possible for our customer to accomplish the same outcome by buying fewer units of our product than they buy of our competitor’s product. Buying less of our product is not the only way a customer can take advantage of our efficiency; they might choose to produce more using the same amount of the two products and generate incremental revenue. But ordinarily, it is natural to compare apples with apples by assuming customer business plans are the same using either alternative. This results in the customer buying fewer units of our product than the reference alternative. This is what we call an “acquisition efficiency.”

Acquisition Efficiency Examples:

|

Whenever there is an acquisition efficiency, there is the potential that sticker shock will create a problem. Acquisition efficiency-related sticker shock is invariably related to units confusion.

Expressing our product’s purchase price in customer units makes a difference. Suppose our testing instrument has double the sample throughput of our competitor’s instrument. Then our customer can buy half as many testing instruments to test the same number of samples. Even if the price per instrument is 30% higher, our instrument outlay per test and our instrument outlay per year are both lower based on the number of instruments purchased. If our tires get 20% higher mileage, our price per mile over the lifetime of the vehicle may be lower even though our price per tire is higher.

Product units result in confusion because our product unit is not equivalent to the competitor’s product unit. Price comparisons are only meaningful if they are quoted in equivalent units. To quote prices per instrument, without being specific about which instrument, tends to be a units shell game that creates confusion benefiting the competitor. With an acquisition efficiency, our testing instrument is not equivalent to the competitor’s instrument. With greater durability, our tires are not equivalent to the competitor’s tires. We can only add and subtract prices and value if everything is quantified in equivalent units. We can only add up elements in a graph if all the elements of the graph are quantified in the same unit.

Unless we frame our conversations in customer terms and customer units, we could miss a source of value coming from our product being more efficient. Analyzing value and price in product units creates confusion and mistakes by adding up non-equivalent elements when there are acquisition efficiencies. What is worse, math mistakes arise from double counting acquisition efficiencies by teams misusing analytical frameworks like Economic Value Analysis® where they display prices as well as value drivers. The best way to avoid mistakes is to make sure the math makes sense in customer-based units.

The positive side of using a customer unit is that it helps drive an essential component of marketing strategy whenever we have an acquisition efficiency. Effective communication of our product’s price in a customer unit helps to move the market’s perception beyond sticker shock if they are used to focusing on price in our product unit. The tire manufacturers realized this when they started communicating price per mile as tires got more durable. The crop protection industry moved to communicating pricing per acre many years ago even though most products are sold by weight or volume.

The positive side of using a customer unit is that it helps drive an essential component of marketing strategy whenever we have an acquisition efficiency. Effective communication of our product’s price in a customer unit helps to move the market’s perception beyond sticker shock if they are used to focusing on price in our product unit. The tire manufacturers realized this when they started communicating price per mile as tires got more durable. The crop protection industry moved to communicating pricing per acre many years ago even though most products are sold by weight or volume.

If marketing is unable to address the sticker shock problem by reframing the conversation based on a customer unit, one alternative is to consider contracting or quoting prices based on a customer-centric unit. This usually involves a kind of guarantee and should be weighed and balanced relative to offering a discount. Both approaches should be unnecessary for buyers doing the math correctly.

Value and price conversations don’t need to be complicated. Framing the conversation with one or several customer units is always a good idea. Flexibility in changing units then helps everyone, internal and external, understand price and value in their own terms.

Value strategies and value selling don’t need to be complicated. Some common sense and a few simple principles help in getting started. Value Propositions provide central content that helps sales teams communicate what our solution does for our customers. For the best enterprises, Value Propositions are a shared basis for sales team collaboration that help sales teams win.

For more information on sales use of Value Propositions see Using Propositions as an Effective Sales Tool

development teams often start by asking, “what is part durability worth per pound of our coating?” When they ask the question that way, they make it difficult to get a clear answer.

development teams often start by asking, “what is part durability worth per pound of our coating?” When they ask the question that way, they make it difficult to get a clear answer. production process or recipe. A pound of plastic can be used to make more auto parts than a pound of steel. Less of a superior chemical additive may be necessary to get the same effect in formulating a household cleaning or personal care product than it takes with the current additive. A food producer may need less of a superior ingredient in a recipe.

production process or recipe. A pound of plastic can be used to make more auto parts than a pound of steel. Less of a superior chemical additive may be necessary to get the same effect in formulating a household cleaning or personal care product than it takes with the current additive. A food producer may need less of a superior ingredient in a recipe. A more reliable or durable product can result in efficiencies by reducing a customer’s need to purchase as much of our product over an extended time frame. A longer lived implantable medical device may need to be replaced less often. A more durable building product may have lower cost over a 50 year horizon to a business not because the price is lower but because it needs to be replaced less frequently.

A more reliable or durable product can result in efficiencies by reducing a customer’s need to purchase as much of our product over an extended time frame. A longer lived implantable medical device may need to be replaced less often. A more durable building product may have lower cost over a 50 year horizon to a business not because the price is lower but because it needs to be replaced less frequently. For equipment producers, acquisition efficiencies occur frequently when one system or machine is more productive than its competitor. A given production target can be achieved with fewer mixing machines. A specified number of lab tests can be performed with fewer high tech testing instruments. A field can be harvested with one combine harvester instead of two.

For equipment producers, acquisition efficiencies occur frequently when one system or machine is more productive than its competitor. A given production target can be achieved with fewer mixing machines. A specified number of lab tests can be performed with fewer high tech testing instruments. A field can be harvested with one combine harvester instead of two.